In exploring the dynamic between “inequality” and the United States’ intellectual property regime, our community must first come to terms about the meaning of “inequality.” As Professor Etienne pointed out in lecture, “inequality” can be harnessed as a tool to stimulate diverse dialogue surrounding our most pressing societal challenges; yet, inequality can also reproduce oppression and violence. In my former “Systems of Inequality” course, as well as in an “Intro. to Anthropology” course, my classmates and I studied and teased out our own definitions of “bad inequality.” I believe that the work of anthropologist Stuart Hall serves to clarify our discussion on inequity: Hall argues that systems of classification and difference, although essential to language and meaning making, become problematic when they become “objects of the disposition of power.” Embracing Hall’s definition of inequality, I would contend that intellectual property laws that stigmatize and cripple the opportunities of certain groups of people, while providing disproportionate advantages to privileged communities, would fall under the category of insidious and adverse inequality.

Joseph Stiglitz and Amy Kapczynski effectively mold Hall’s generalized definition of inequality to fit into our class discussion about intellectual property: “IP regimes as currently configured in fact make IP a mode of power that is particularly inaccessible to those with few resources” (Kapczynski). In Joseph Stiglitz’s article, the disadvantaged groups are those who occupy the lower income bracket and cannot afford to participate in Myriad’s breast cancer gene testing, and thus have a less equal chance to conquer cancer and to survive. The Myriad case spotlights an intellectual property design that again fits Hall’s definition of inequality; holding patents over genes can be recognized as a “system of classifying different recipes of knowledge” that ultimately disadvantages, and perpetuates the suffering of, low-income women. The Myriad case, if passed, would be a form of structural class domination, reproducing unequal access to health and privileging the lives of those who are able to pay for testing and treatment.

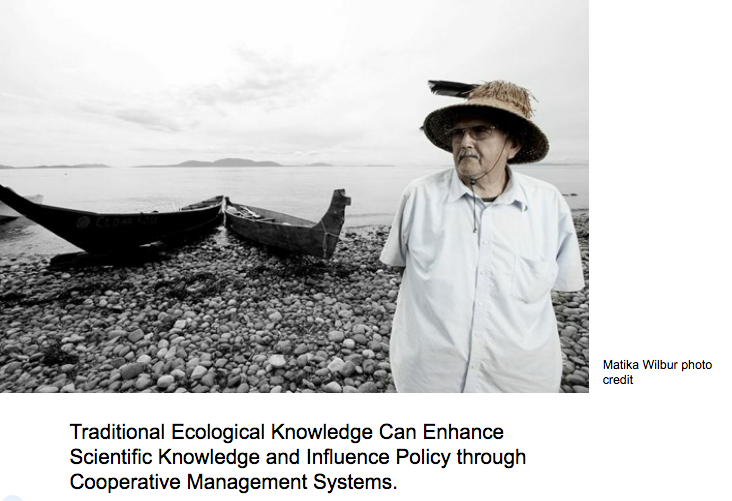

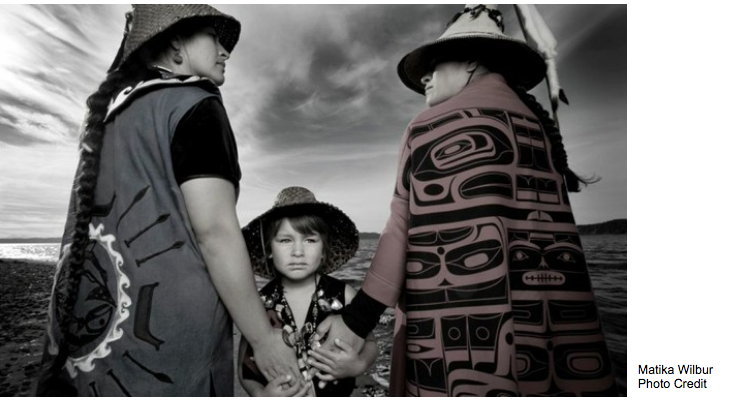

Amy Kapczynski further explains this phenomena by providing a “market ordering” scenario: “market ordering will allocate a loaf of bread to a rich person who is “willing” to pay $6 for it, rather than to a poor person who is “willing” (read: able) only to pay $1 for it, even if the poor person would get far more pleasure from it, or indeed would need it to survive.” Kapczynski then adds to Stiglitz’s article by underscoring the existence of “substantial literature that criticizes IP as excluding ‘poor people’s knowledge.’” This point in particular resonated with me. In my Systems of Inequality course, I conducted research on the ways in which North American indigenous communities generate knowledge about the natural environment. Their forms of knowledge production, however, are often unrecognized and even violated by dominant manufacturers of knowledge: those who hold privatized patents over ideas and information. If a privileged few hold and manage the legal rights to knowledge, America’s most marginalized minds and voices will continue to be silenced; and, the oppressive historical trend of disregarding Native American ideas is survived through the intellectual property system. The tragedy of this imbalanced access to knowledge is that a multitude of North American indigenous communities have developed sustainable food production, distribution, and processing techniques, as well as learned how to maintain complex ecological balance with the landscape. I’ve included some powerpoint slides from Gail Small, a professor of Native American Studies at Montana State University and a member of the Northern Cheyenne Tribe, below.