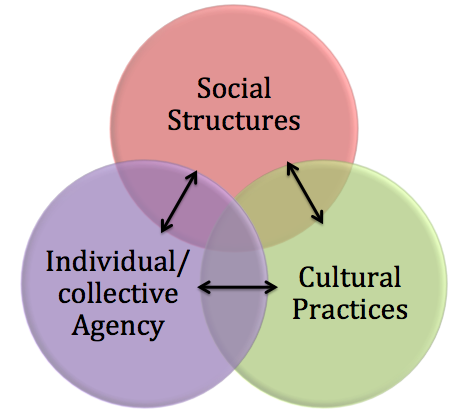

Prior to taking an open source public policy class, I thought that product innovation was inextricably connected to the protection and privatization of design blueprints. This widely held misconception has survived as a result of the normalized belief that humans are self-involved creatures driven by the sole promise of making a profit. I believe that my personal inability to grapple with the concept of public open source design platforms is due, in part, to the individualistic culture that I grew up in. The research I have conducted throughout this course has led me to believe that human beings do not make decisions in relative isolation. Humans are attuned to the actions and feelings of other human, as well as nonhuman, living beings. Thus, the decisions we make are also a product of our relationships with other people, as well as a result of situations external to our own needs and wants.

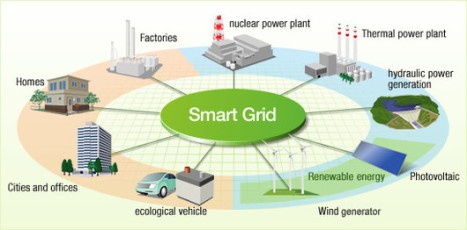

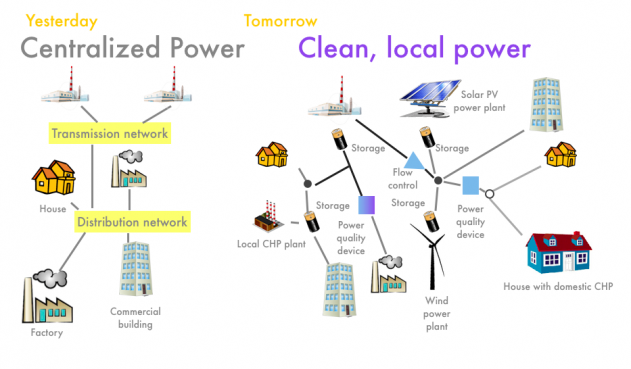

However, I have also reached the conclusion that an individual’s reasoning for adopting open source strategies is not entirely altruistic, either. For example, if an individual chooses to release the design recipe for their break-through, innovative sustainability technology, they will eventually generate economic returns to their innovation. If an entrepreneur releases the design blueprints for his or her new and sustainable energy grid technology, the entrepreneur will speed up the grid’s costly and time-consuming production and installation processes. As other competitors begin to customize and replicate the entrepreneur’s innovation, the competitors will also be contributing to the expansion of the product’s market, which in turn will provide more business for the innovative entrepreneur. And, if the same entrepreneur calculates the social cost of not expanding the sustainability market, our entrepreneur will be able to quantify the dollar value created by his innovative clean energy grid. Since our entrepreneur is a human being that exists within society (and will therefore benefit from the positive impacts of a cleaner environment), reduced societal costs means a reduction in his own personal spendings.

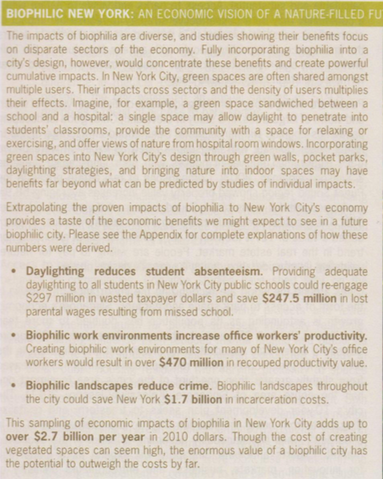

What helped me formulate and then articulate this argument is the energy group’s open source project on the Vinegar Hill community. As a member of the social subcategory of the renewable energy group, I conducted research that quantified the social costs of continued fossil fuel use. I also had to synthesize the data on a cohesive PowerPoint and then teach and present my findings, which served to concretize my knowledge of open source concepts. For example, I found a multitude of evidence-based articles and research reports that proved how greener environments and increased exposure to the natural world is linked to children’s’ cognitive development, mitigating symptoms of ADD and ADHD (Jacobs). I also found a myriad of research demonstrating how green cities enhance intellectual development and reduce mental health disorders, such as depression and anxiety (Taylor, Kuo and Sullivan). I accumulated case studies that outlined a list of economic arguments for renewable energy, which is illustrated in the screenshot below. Finally, researchers and scientists have established a causal relationship between ceaner air and physical health: “results from the Harvard Six Cities Study show that when adjusting for other health risk factors, particulate air pollution in the U.S. is associated with mortality (Dockery et al., 1993). And when air pollution decreases, “hospital admissions for pneumonia, bronchitis, and asthma also decrease” (Pope, 1989).

Faber Taylor, A., Kuo, F.E., & Sullivan, W.C. (2001). “Coping with ADD: The surprising connection to green play settings.” Environment and Behavior, 33(1), 54-77.

Kuo, F.E., & Faber Taylor, A. (2004). “A potential natural treatment for Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder: Evidence from a national study.” American Journal of Public Health, 94(9), 1580-1586.

Faber Taylor, A. & Kuo, F.E. (2009). “Children with attention deficits concentrate better after walk in the park.” Journal of Attention Disorders, 12, 402-409.

Medicine, Institute of., et al. Public Health Linkages with Sustainability: Workshop Summary. National Academies Press, 1900.

“Biophilic Design Case Studies.” Terrapin Bright Green, http://www.terrapinbrightgreen.com/report/biophilic-design-case-studies/